Photo credit: Colonia Guerrero, Mexico, Agroecology Map Gallery

The concept of co-creation, which reflects the desire to create a fairer, more sustainable and socially connected societies, is central to agroecology.

Current food systems knowledge is standardized

Current food systems rely on top-down transmission of standardized “technical packages” rather than inclusive and context-specific solutions. As a result, traditional knowledge—particularly from Indigenous communities, who are custodians of 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity—is often overlooked. This lack of integration between traditional wisdom and modern innovations limits the capacity to develop new solutions.

On the other hand, agroecology, both as a science, a practice and asocial movement (Wezel and al, 2018), aims to transform food systems by emphasizing the co-creation and horizontal sharing of knowledge, integrating local and scientific innovations, particularly through farmer-to-farmer exchanges (HLPE-CFS, 2009).

What does co-creation mean?

Central to this concept is the inclusion of citizens as active partners who hold valuable resources and skills for society. Co-creation is not confined to a top-down or bottom-up approach, instead, it requires multi-directional collaboration.

Indeed, co-creation of knowledge involves the interaction of different cultural perspectives and learning methods. According to Francisco J. Rosado-May, professor at the Universidad Intercultural Maya de Quintana Roo, Mexico (UIMQRoo, member of the Agroecology Coalition), intercultural co-creation of knowledge “is the result of a process where different ways of learning, creating, innovating, and transmitting knowledge coexist in a safe environment, allowing conditions for new knowledge to emerge”. Therefore, this concept fosters collaboration between scientific and Indigenous knowledge systems.

The need for transdisciplinary and diverse knowledge systems

Transdisciplinarity, a key methodological approach for addressing complex socio-environmental issues such as climate change, food security, biodiversity loss, and social inequality, is closely linked to co-creation. Addressing these challenges requires diverse academic and non-academic stakeholders, including Indigenous communities, farmers, and fishers, who have a deep understanding of local ecosystems and the interconnection between biodiversity and livelihoods (OECD, 2020; Ludwig et al., 2023). Indigenous communities have an articulated expertise on biodiversity and ecosystem dynamics (Chilisa 2019). Nevertheless, Indigenous knowledge is often dismissed as “pseudoscience”, undermining its credibility and relevance. This lack of recognition has severe negative implications for these communities. Indigenous territories are disproportionately impacted by food insecurity and biodiversity loss, as current food production systems neglect their expertise. Consequently, Indigenous lands are appropriated for large-scale farming, traditional labor is replaced by mechanization, and local crop diversity disappears and with it the resilience to unforeseen events such as droughts, deforestation and soil erosion (Vijayan et al. 2022). Moreover, from the research point of view, Indigenous expertise has not been widely investigated, except from indigenous scholars and some notable exceptions in feminist and decolonial scholarship (D. Ludwig et al., 2023). Nevertheless, there have been some important recognitions. For example, the Yucatec Maya’s ich kool (milpa) agricultural system has been recognized as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS) by the FAO due to its sustainable knowledge and practices.

The Learning by Observing and Pitching In (LOPI) example

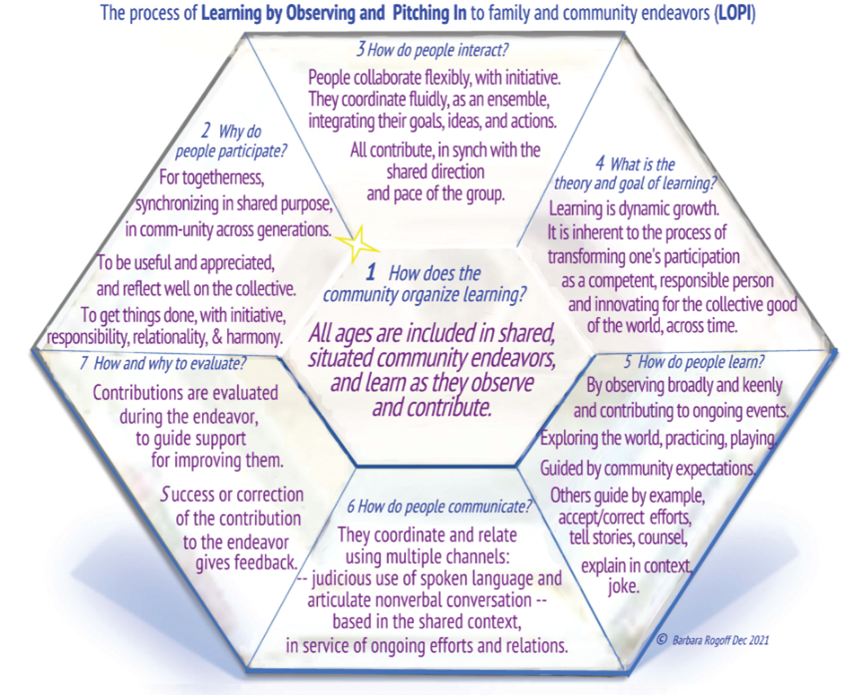

The inclusion of diverse knowledge systems is essential for transforming food systems. Indigenous ways of learning, such as “Learning by Observing and Pitching In” (LOPI), emphasize community-based contributions (Rogoff 2014). Rogoff’s (1990) concept of “guided participation” highlights how community involvement shapes individual learning, making it a mutually constitutive process. Rogoff and colleagues represent LOPI as a holistic model with seven interconnected facets.

Community values, practices, and ecology are central to the LOPI learning approach. In Indigenous communities, people of all ages share spaces, learning through observation and participation. A core example is the Mexican value of being acomedido/a, which promotes relationality, reciprocity, responsibility, and respect. Practitioners of this value remain alert to community needs and take initiative to help without being asked (López et al., 2012). Similarly, in Tzeltal communities in Chiapas, Mexico, consensus and reciprocity are central to governance. Land is communally owned and distributed among members, who are then responsible for participating in decision-making and consensus-building processes for nearly all local political matters (Rogoff, Mejía-Arauz, 2022).

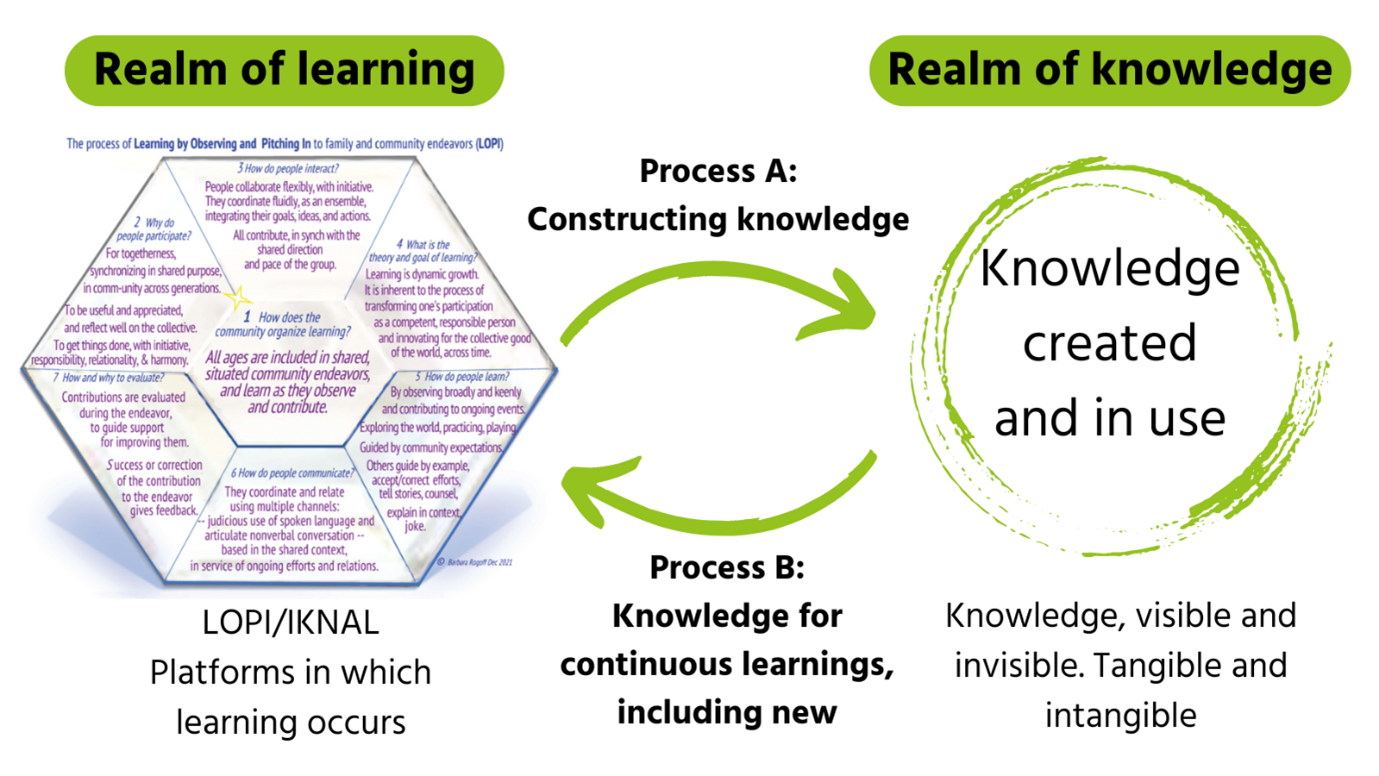

Researcher Francisco J. Rosado-May explains the process of creating intracultural knowledge in Yucatec Maya as follows:

Process of learning and constructing knowledge (Francisco J. Rosado-May)

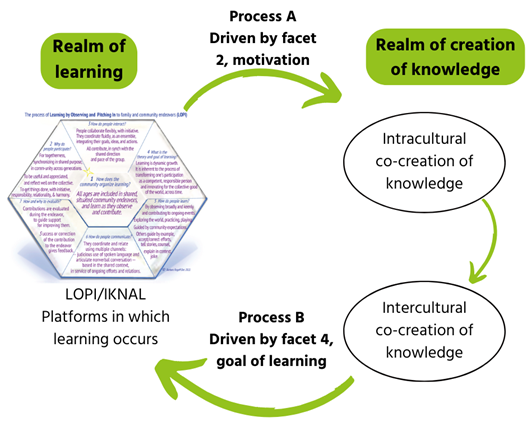

In the Yucatec Maya, effective intercultural co-creation requires a solid training on intracultural co-creation and motivation is crucial to move from learning to creating knowledge.

Process of learning and constructing knowledge n.2 (Francisco J. Rosado-May)

Agroecology & the co-creation of knowledge

Agroecology considers co-creation as essential for transforming food systems and implements concrete example of activities fostering it, such as:

- Platform for the horizontal creation and transfer of knowledge and good practices (e.g., farmer to farmer learning and exchanges including farmer field schools, farmers’ climate field schools, community of practices on agroecology)

- Farmer research and experimentation groups

- Recovery, valorization and dissemination of traditional and indigenous knowledge

- Co innovation between farmers and researchers / participatory research / transdisciplinary research (design, implementation, analysis, evaluation)

- Improved access to agroecological knowledge (e.g., capacity building/strengthen agroecological extension, improvement and development of agroecology curriculum, consumer food and nutrition education

- Engagement and participation of producers and consumers in local community and grassroots organizations

To conclude, addressing the significant challenges of our time requires a transdisciplinary approach that integrates all forms of knowledge. Ancestral knowledge, developed over centuries and deeply rooted in the expertise of Indigenous populations living in close connection with nature and biodiversity, must be acknowledged and revalued. The exchange between traditional knowledge and contemporary ideas – often driven by young people and promoted through agroecological approaches – can lead to the co-creation of new solutions and innovations. These innovations can be crucial in transforming our food systems in a sustainable way.

Check also this interview with Francisco J.Rosado-May filmed during COP 28 on Climate in Dubai in 2023!