The next 18 months offer a catalytic opportunity for countries to integrate agroecological principles in their national climate and biodiversity strategies, and for agroecology to secure its place in the global climate agenda.

By November 2025, when Brazil hosts the 30th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC COP 30) in Belém, member states must revise their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – creating a set of ‘NDCs 3.0’ into which a growing number of actors support the embedding of agroecological principles. And by October this year, when Colombia hosts the 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP 16) in Cali, countries are expected to update their National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs).

The pivotal role of National Agroecology Frameworks to help states grasp these opportunities and unlock investment and climate finance for agroecology was the topic of a panel discussion on 3rd June 2024 at the 2024 Bonn Climate Change Conference (SB60).

Here are some highlights:

Agroecology can play a crucial role fostering synergies between all the Rio Conventions and their tools, Oliver Oliveros, Coordinator of the Agroecology Coalition and head of the Coalition Secretariat, argued in an opening video address. Climate change, biodiversity loss and land degradation are closely interrelated. And as a science, set of practices and movement that is holistic and integrated in its approaches, agroecology “allows us to really reach economic, environmental, climate, health, social and cultural objectives simultaneously,” he stressed.

“The very fact that agroecology is now being enshrined in national policies and by governments, both in the North and in the South […] is a testament that the time for agroecology has arrived,” Oliveros stressed. “We cannot be at a better moment than now.”

Growing momentum

Although a WWF study from 2022 assessing NDCs revealed that only 15 member states then mentioned agroecology in their NDCs, momentum is now building for agroecology to be integrated in governments’ agricultural and climate polices, as well as in international agreements, noted Martina Fleckenstein, Global Policy Director for Food at WWF International and moderator of the discussion. For example, Target 10 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework flags agroecology as a biodiversity-friendly practice.

Several countries in eastern and southern Africa are also developing National Agroecology Strategies containing interventions that can contribute to national climate objectives, noted Moritz Fegert, Project Officer at Biovision Foundation. For example, Tanzania launched in November 2023 its National Ecological Organic Agricultural Strategy, and Kenya, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe are slated to follow suit by the end of this year. The participatory nature of these frameworks – which are drafted with input from a diverse range of actors, including farmer organisations, agronomic institutes, private sector actors and civil society organisations promoting the protection of the environment, representing consumers and marginalized or underrepresented communities – should make them easier to implement, he added.

Martina Fleckenstein (WWF) and Moritz Fegert (Biovision), Berlin room, UN Campus Bonn

Picture credits: Genna Tesdall/ YPARD

Integrating agroecology in the NDCs

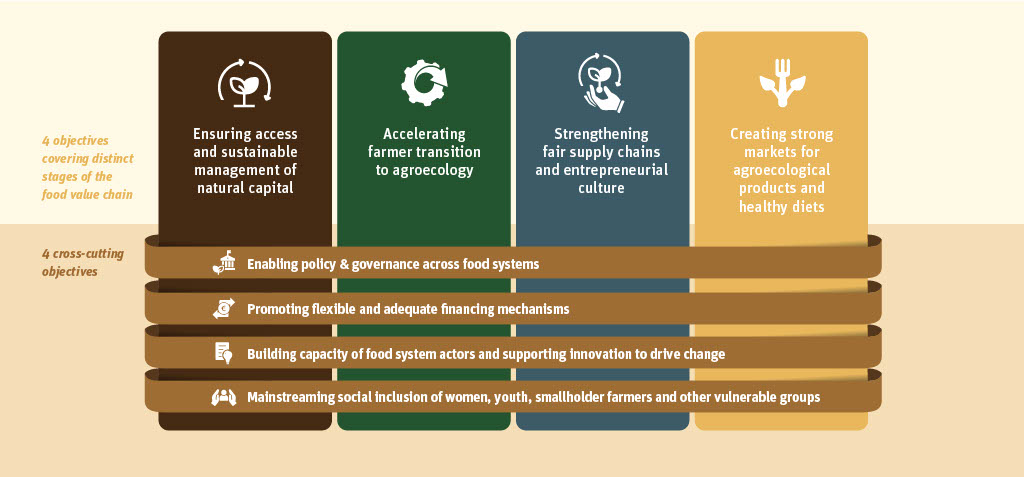

Initiatives like these can help countries coordinate actions to deliver on their objectives around climate mitigation and adaptation and fighting biodiversity loss and land degradation, Fegert argued. Based on the above countries’ experiences, Biovision has developed a set of objectives that can help other governments embed agroecology into their updated NDCs (see figure below).

4×4 framework of strategic objectives, in “National Agroecology Strategies in Eastern and Southern Africa“

WWF and partners have developed an interactive web-based guidance tool for food and agriculture, Food Forward NDCs, that includes concrete policy measures to help countries integrate agroecology in their NDCs, noted Fleckenstein.

Countries’ progress

But where do countries stand in the process? In the case of Germany, for instance, the main pathway for integrating agroecology in its NDC for agriculture is its recently adopted 2030 Organic Strategy, which aims to increase organic farmed agricultural land in the country to 30% by 2030 and includes measures to support agroecological practices and approaches, according to Alexander Lingenthal, Senior Policy Officer at the country’s Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). National policies like this enable countries to build a reliable political framework for both public and private-sector actors to invest in agroecology and to define context-specific implementation, he said.

It is also vital that countries like Germany increase their support to partner countries in developing and implementing agroecological strategies and policies, Lingenthal added. For example, the Knowledge Centre for Organic Agriculture and Agroecology – a global project implemented by the German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ) – can help bridge knowledge gaps along the agricultural value chain to assist farmers transitioning from industrial farming.

The Agroecology Coalition offers member countries guidance and a common path to integrate agroecology into their national strategies and policy instruments like NDCs and NBSAPs, added Lingenthal. Both BMZ and Germany’s Agricultural Ministry are now members of the Coalition.

“We have to show that sustainable transformation of agriculture and food systems is essential to jointly address climate, soil and biodiversity crises, that we need activities that deliver to the goals of all the three Conventions, and that agroecology is an important holistic pathway to achieve this,” he said.

Brazil – which has successfully integrated agroecology in many of its policies and programmes aiming at a sustainable transformation of its food system, especially via its National Policy for Agroecology and Organic Production (PLANAPO) – could offer an example to follow. PLANAPO comprises a series of programmes – ranging from the National Program of Native and Creole Seeds and Seedlings for Family Farming to the Food in Schools National Program – explained André Moreira Bordinhon from the country’s Ministry of Agrarian Development and Family Agriculture. He noted that, in line with agroecological principles, these were developed with input from 14 ministries as well as farmer organisations and civil society groups.

An agroecological transformation of the country’s food system will also be a key element of Brazil’s NDC 3.0 goals to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions according to set targets: -48.4% by 2025, -53.1% by 2030 and achieving neutrality by 2050. “We need substantial changes in the way we produce, consume and distribute food to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and keep our ecosystems preserved,” Bordinhon said. “We’re making an effort in our ministry to give agroecology the role it deserves in this agenda.”

In Costa Rica, multi-stakeholder collaboration – guided by government institutions related to agriculture, the environment, health and finance, and including the active participation of producers and other private-sector actors – will also underpin the country’s efforts to embed agroecology in its updated NDCs, added Roberto Azofeifa, Chief of the Agroenvironmental Production Department at the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock.

Strengthening consumer demand and access to agroecological produce is central to Costa Rica’s strategy, he noted. For example, the country’s participatory guarantee systems make it cheaper for farmers to access consumer markets and satisfy consumer demand. In countries like Costa Rica, where tourism is an important part of the economy, cross-sector initiatives should also target synergies between sustainable tourism, production and consumption, Azofeifa recommended.

Through the 13 principles of agroecology, “it is totally possible to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and build nature-based solutions for development on sustainable production and consumption systems, as well as resilient communities with the capacity for adaptation to climate change,” he said.

Saskia Sanders, Policy Advisor for sustainable food systems at Switzerland’s Federal Office for Agriculture, took a similar view, arguing that agroecology can be scaled in support of countries’ climate change mitigation and adaptation objectives by “establishing stronger links between sustainable production and consumption, building regional and local supply chains, and fostering a consumer behaviour that takes into account the planetary boundaries.”

Switzerland is currently working on the development of its agricultural policy beyond 2030, aiming to evolve it into a food systems policy incorporating essential elements of agroecology. This forms a key element of its ongoing work towards including agroecology in its updated NDCs, according to Sanders.

To this end, Switzerland has defined three goals, around agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, the climate footprint of food, and the creation of resilient practices to enhance food security, she explained. Proposed measures include voluntary agreements with retailers to promote sustainable production and consumption, the strengthening of social security protection for farm workers, and notification requirements for fertilisers and plant-protection products to improve transparency around the use of environmentally relevant additives.

Genna Tesdall, Director of Young Professionals for Agricultural Development (YPARD) and board member of the Food and Agriculture for Sustainable Transformation (FAST) partnership, called for young people to be given a greater role in advancing climate change mitigation and adaptation through agroecology.

Panelists: Genna Tesdall (YPARD), Saskia Sanders (Federal Office for Agriculture, Switzerland), Alexander Lingenthal (Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development, Germany) – online: Roberto Azofeifa (Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, Costa Rica), Dr. André Moreira Bordinhon (Ministry of Agrarian Development and Family Agriculture, Brazil), Berlin room, UN Campus Bonn

Picture credits: Moritz Fegert/ Biovision

The agriculture sector is the main employer of young people in the Global South, making them a potentially key lever for food systems transformation. But with their work often informal, precarious, and poorly paid, young people working in the food value chain first need access to resources, education and networks, plus an enabling environment, Tesdall argued.

“We should support youth as the leaders of today and tomorrow, so that we can make agroecological transitions happen for climate mitigation,” she stressed. “That would be my main call to action for folks – involve young people: at the table, talking; and in the fields, doing.”

Unlocking finance

For agroecology to be implemented at scale and for food systems to withstand challenges related to climate finance and biodiversity, more financing is urgently needed – ranging from climate finance and government spending to private-sector investment, panellists argued.

Germany has increased its financial commitment to agroecology by around €800 million since 2014, noted Lingenthal. For example, the Indo-German Lighthouse Initiative on Agroecology has unlocked around €300 million of financial and technical cooperation in support of Natural Farming programmes and strategies in India. Germany has also supported governments such as Kenya’s to develop soil management policies.

Climate finance to food systems has actually decreased in recent years while rising inequality is eroding both individuals’ resources and the tax revenue that governments can invest, noted Tesdall. “Those are two huge issues that we need to tackle as fast as possible.”

The redirection of subsidies that support harmful agricultural approaches and exclude young people from food systems could help free up resources, she argued. Fegert too proposed that opening up chemical fertiliser subsidy schemes to alternatives such as bio-inputs could greatly impact countries’ climate mitigation objectives.

Costa Rica benefits from a national government budget to support agroecological implementation, as well as financial support from partner governments and private-sector investment, but more non-refundable financing mechanisms are needed, said Azofeifa.

To attract more private-sector resources, he stressed the importance of awareness raising about the profitability of agroecological approaches as well as their environmental and social benefits and of demonstrating these with concrete examples.

Asked what opportunities he saw for Brazil to fund agroecology through the Rio Conventions, Bordinhon noted that the country has already developed several state mechanisms for investing in agroecological practices, most notably via PLANAPO.

For example, the National Program for Strengthening Family Farming provides funding for agroecological and organic production as well as agroforestry. And the EcoForte grant programme – using direct funding from public banks in Brazil to support agroecological and organic farming networks throughout the country – is slated for launch this summer.

However, while agroecology is gaining recognition and more initiatives are being launched to support it, “the level of resources are not yet commensurate to the recognition it deserves and to be able to achieve its full potential,” said Oliveros. To this end, the Agroecology Coalition will continue to push for increased investments to allow agroecology to flourish.

The event was co-organised by the Agroecology Coalition, Biovision Foundation, the Global Alliance for the Future of Food, IPES-Food, the South Asian Forum for Environment (SAFE) and WWF.

A recording of the event is available below:

Banner picture credit: Evans Ogeto